Go West

You can only miss a place once you leave it, that said the Western States have a calling that is hard to describe. It’s not just the landscape that is different. There is a feeling that anything could happen and everything is moving. Photographs feel historical and the future looks brighter.

Making any images on the road is often tricky as you often don’t have the time to wait around for light to change or spend all day looking for good compositions. But often the real joy in photography is having no agenda, just a camera and the process of looking. Its a wonderful thing..

Go West Life is peaceful there

Go West In the open air

Go West Where the skies are blue

Go West This is what we're gonna do

Drive

Mojave 2020

The invention of the motor car paved the way for photographers in America and the road trip was born. Nowhere else in the world can one get in a car and just drive thousands of miles with the freedom to go pretty much anywhere. Throw a camera in the mix, its easy to see why I made the US my home.

Since my early beginnings as a photographer I have been making road trips with a camera. The first photograph I ever made was on a return trip from Scotland with camera given to me on my 10th birthday. Years later when I passed my driving test in the UK, the first thing I did was grab my camera, borrow my fathers car, and headed for the mountains. Thirty years on, the destinations may have changed, but the drive remains the same.

Where’s my plant?

There are often times when I'll make a photograph that has nothing to do with my photography. It's just a record of something that exists. But often, these images, over time, can become something more. I made the image of the 'plant theft' sign because I found it funny that someone loved their plant so much that they made a sign. But looking at it now, I did make it at a time of day when the light was nice and composed to show the sign at its best. The image below is similar in that someone made a sign, albeit much more aggressive, but again, the light is nice, as are the clouds. I am not stating for a moment that these snaps should find there way onto a gallery wall, but there is something appealing about this kind of imagery.

I have always found signage interesting because we can interpret it as funny, aggressive, passive-aggressive, nonsensical, clever, and sometimes just plain silly; therefore, they may have something to do with my photography after all.

The camera as a tool.

Panoramic 617 film camera. Still works.

For anyone wanting to buy a used camera, I would always tell them never to buy one from a professional photographer. This is especially true of landscape photography, where cameras are subject to rain, mud, snow, and sand. My 617 panoramic camera, (now more tape than actual camera), has been dropped in the ocean, bounced off rocks, driven over by a jeep, and thrown out of a moving car (well actually dropped while trying to photograph a storm). The idea of spending tens of thousands on a camera and then going on a landscape jolly is something I prefer to avoid. No matter how careful you are, the wind may blow, or the tree limb snap when you least expect it. But at the end of it all, the camera is, first and foremost, a tool. It was never intended to serve as a pendant of wealth and prosperity, as some cameras often do.

The joy of photography will always come from creating something. From that special moment when we know we have something good, to seeing an image published, or on a gallery wall. I will always have a bee in my bonnet for camera manufacturers and their ploys to have you buy their latest piece of plastic. There is nothing worse than someone spending oodles on a camera because they believe it will make them take better photographs. Actually, there is; spending oodles on a camera and never using it.

Don’t Ask.

Caddy Scrapyard, 2020

I always encourage students and youngsters to contact photographers they admire and obtain firsthand information. It was a big deal back when I was at college as you had to either write a letter or get them on the phone pre-cellular. What always surprised me was that I always got a reply. In fact, two of the photographers are still on my mailing list, and over the years, I have kept up communications with them, which was particularly helpful once I began lecturing and teaching. But the one thing I learned was that you could never just ask a photographer, how do I get a job? Or how do I make money from photography? Maybe it's because a photography career is not as straightforward as other jobs, as there are many routes into the profession, but it's still money in and money out.

I remember asking a photographer how they achieved such a dramatic effect in their lighting, to which they replied, "Why would I tell you in ten minutes what has taken me ten years to perfect." This response may seem odd in an online digital age where everyone's a photographer and has a YouTube channel. But twenty years ago, you had to invest time with a photographer before asking such things. One must also realize that many photographers want to stand out. To do so, you cannot throw your tried and tested methods around for others to use willy-nilly.

It is true, particularly in a student environment, that you will always get asked a 'how to' question. Having been on both sides of the fence, I always refer to the day I asked my favorite landscape photographer, "What advice do you have for a photographer trying to break into the market?" His response was to "open a candy shop." Since then, I have never asked the question, but would probably give a similar response.

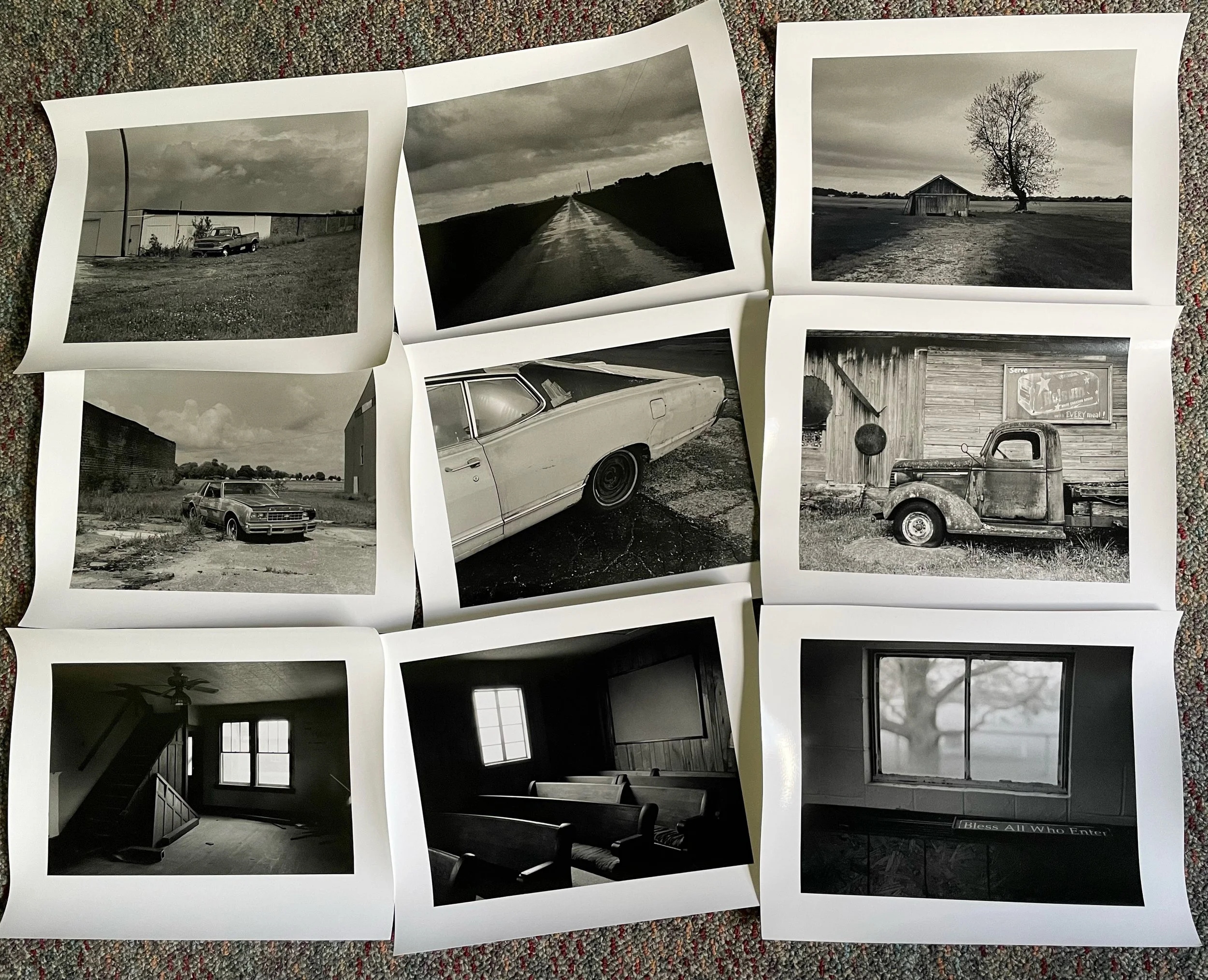

Elvis has left the building.

Having spent three winters in Middle America, the thought of heading back West is a joyous one. Despite an abundance of photographic material in a place I came to refer to as Middle Earth, I have never felt a connection to the place. For the first time since moving to the States, I felt like a foreigner, especially when locals have no idea where I am from. But then again, why should they? Unlike the West, I doubt there will be any calling to return, despite the joy of zipping around and photographing old barns and rusty wrecks.

How I came to be here is still a mystery and a day has not passed when I didn't ask myself, what am I doing here? Despite this, I have amassed more photographic work here than anywhere else. No matter where you are, there will always be something to photograph, even if it's just to say I was here or I was there.

The image above was made on the day of my arrival in middle America, and I took it as a sign of hope. Sadly, there was none, and Elvis has definitely left the building, as have I.

I, am an artist..

Death Valley, 2017

Nowadays, the term photographer is just too broad a title, especially considering the vast range of ‘photography’ it can cover. From images made on 8/10” film (above) to the tiny camera on an iPhone, to compare such devices is as vast as Death Valley itself (see above), albeit they produce the same thing: a photograph made by the photographer.

If I call myself a photographer, I will be asked to take pictures of weddings, kittens, and my neighbor's doll collection. If I say I am a landscape photographer, the conversation usually stops there. But even 'landscape' is too broad a title as one imagines rolling hills, flowing streams, fluffy clouds, and maybe a rabbit in a field, all of which I do not photograph unless they are hills littered with dumped cars, streams full of pollution, or rabbits driving old motor cars.

Long ago, it was easy as photographers only photographed three things: Landscapes, people clothed or unclothed, and inanimate objects like a manky pepper. Back then, the term photographer was enough because, unlike today, hardly anyone called themselves a photographer.

As a result of everyone now being a photographer, the term artist is often used to describe someone working with photography, or rather Fine Art Photography, as their medium. Perhaps a good solution for someone like myself, but I wonder how long it will be before everyone calls themselves an artist.

The talent-less Mr Rigsby

November 2023

When I was 14 years old, I spent a week with the local newspaper photographer for my work experience. Having already had access to the schools darkroom, I had spent a fair amount of time shooting and printing mostly black and white landscapes and jumped at the chance of seeing the workings of the newspaper. Mr Rigsby, the main photographer, was a lovely chap full of worldly wisdom and good advice for a young cocky wanna-be photographer such as myself. I had secretly expected a little bit of excitement, maybe a murder or a car chase, but the most exciting story of the week was the county's oldest dog turning twenty-one, a scruffy border terrier whose name I forget. As my week ended, Mr Rigsby handed me several rolls of blank film and told me, "Just remember son, you cannot make a living photographing landscapes." Well, respectfully, he was wrong and would later eat his words when I had an exhibition at the local library and sold a print for twenty pounds. Huge profits aside, my week with Mr Rigsby was a learning experience in that no matter how wise you may be, you should never assume anything, especially when it comes to photography.

These days, my work is a far cry from my early black-and-white landscapes. They are often color, shot at night, and not very pretty, but always for sale. Mr Rigsby would not approve.

No one can do what you can do.

The Flowery Room 2012

How we feel about a photograph often changes over time, as can the narrative. When I made the Flowery Room series during my master's, I had no desire to experiment or find new ways of approaching work. I wanted a straightforward approach, working in a familiar way.

Much to the despise of my then mentors, who suggested I experiment with photographs of kittens, I wanted to do a project on memory. It was not an attempt to recreate a memory but to produce work that would help me remember places I knew as a boy growing up in the north of England. Having visited my homeland recently, after a ten-year absence, I can see that the places above have changed dramatically or are gone completely. My original idea had worked, although it did take a decade to realize.

Doing this project was undoubtedly a life lesson to stay true to what moves you to photograph. After all, no one else can do what you do.

Photography and Truth

I have always tried to teach that truth in photography does not come from the photograph itself but from the person who made it and that a photograph is just a photograph. But people will always try to convince us otherwise. When photography was invented, the problem was convincing people that the physical picture was real. Once people came around to the idea that you could capture someone's 'likeness' in a photograph, they would often believe what the photograph was telling them. Of course, that didn't stop early photographers from trying to fool people, especially when things like spiritualism were rife during the 1850's.

We are programmed to believe what we see in a photograph as truth, none more so than documentary photography. Despite this, it took several years for newspapers to realize that the only way to combat adjusted digital files was to accept RAW images. All fine and dandy for printed matter, but what about online content? In short, the digital image can never be trusted to give us a more 'truthful' image. AI has added a new layer of lies to what we consider truth in an image, in that there will most likely come a time when we cannot tell the difference between reality and fiction, never mind whether it's true or not.

The only way we can get back to some truth in photography, and by this, I mean documentaries and telling the world what's going on, is to go back to film; Light and shadow captured onto film and printed. Yes, there will always be some manipulation, cropping, or angle of view, but it's better than the fake world we are heading for. Photography has often gone full circle, be it returning to film, or refusing to Photoshop, but unfortunately, we have turned a corner onto a one way street.

Technology has always been the driving force behind the way we make photographs. Wet Plate, Dry Plate, Sheet Film, Roll Film, No Film, you get the idea. Photography has, and always will be, about the next new thing because the market is driven by the amateur, not the professional. A professional will find a method and stick with it, often producing a style and way of working. An amateur will always want the next thing, often believing a new camera will make them a better photographer, something which has always rubbed my rhubarb.

Since my early beginnings as a photographer I seem to have been a little late to the party, entering the world of black and white printing around the same time digital photography started to raise its pixelated head is one very good example, but photography has always been a constantly changing medium.

I remember dabbling with infrared film back in the late eighties. At the time everyone seemed to be using it to create otherworldly images of trees and clouds. All you had to do was set the camera to the correct settings for IR which were not from your light meter and move the focus slightly (there was a dot on the lens for this think). But fundamentally, it was the film that created the effect. Does this mean that because the photographer does not have full control, it is a lesser technique? of course not. But there is the danger of allowing technique to rule over substance in our photography.

Leica cameras are a fine example of how the market is driven in photography. There are plenty of other cameras on the market, but a Leica is considered by many to be the camera of the professional. Leica’s were the first cameras to lead the way for roll film and therefore photo journalists and documentary photographers. Any serious photographer back in the 50’s used a Leica. Their pedigree is like non other. They were mechanical, tough, and of the highest quality, built for reliability and to be used. Today the Leica is still of the highest quality, but its not the professional photographers lining up for the next model, its the keen amateurs. My issue is not with the Leica itself, I have two, digital and film, and love them like children, it is with the newer Monogram versions aimed at the photographer who has always worked in black and white film. These Mono cameras work in a way that produces the most wonderful tones and contrast that only a master black and white printer could produce (and that’s pushing it). My argument would be that the photographer has lost some of the control over the image and it becomes all about what the camera can do. Like it or not, the camera is making decisions for us. OK, its not fully automated like a camera phone, but its not far off either.

We think that photography today is so easy that anyone can be (and does call themselves) a photographer with cameras that you can just point and shoot. But this concept is really no different from the Kodak Box Brownie invented 123 years ago along with the slogan, ‘You press the button, we do the rest.’ This mindset of technically difficult is professional, and easy is amateur will always remain debatable. Its about whats in the package, not just the delivery.

The Double Edged Sword.

I have been teaching in some capacity for around 25 years. At first, it was Photography Workshops in Europe and the USA, Switzerland, Cuba, Africa, Asia, and even England. From there, I went into education, which, despite having some similar content (like making photographs), it was a very different approach. My photography degree was done at an art school when photography was a trade you learned, and printing was a thing you did with stinky chemicals and safe lights. Once the Art Schools switched to Universities, much of the practical was replaced with academia, dramatically changing photography education. Despite being a keen writer and self-proclaimed photo theorist, I loathed the thought of taking a practical visual medium into some essay-based topic.

These days, the issue with an art degree is that often, students will need more preparation for the world outside the academic bubble. They may have the skills to make good art or photography. Still, if they lack the know-how to make money from it, fund it, or do something else that enables them to continue making their art, then we can be pretty sure their time in education will become nothing more than a memory with a few photographs thrown in.

When I started teaching, an old mentor friend said, "Teaching is like a double-edged sword. You know what the students need, but there's always others calling the shots who might think otherwise." At the time, I thought he was a little jealous of my newfound interests or the book I had just published, but now, looking back at my own experiences, I know he was right.

Education in photography isn't declining; it's increasing. Just not in the way universities would like. Here's how I like to explain it;

A 'proper' personal trainer will become certified. They will study and learn all there is to know about training and usually specialize in a particular field. Then, and only then, they will begin to train people using their knowledge. However, there will always be those that fancy themselves as a personal trainer. They will watch a few videos online and pick up a few tips from fellow gym enthusiasts who have also been watching videos online. They are not certified and have failed to study the core training basics. They get a few clients at the local gym where, eventually, someone pulls a muscle because they didn't know if you bend something a certain way, things can happen that you did not know about. The person they trained then goes off and starts to teach someone else, and then that person trains someone until everyone has pulled muscles. If we think of the 'proper' trainer as a qualified teacher (with experience in the job, not just a degree) and the enthusiast as someone who has made a few images and is now a 'vlogger,' you get the idea.

Despite technology changing how people are taught photography, the fundamentals of it will always remain. No one needs a degree to take photographs. And therein lies the problem of education.

Night and Day

Having worked in the twilight for some time now, I still cant quite put into words the feeling one gets after the sun goes down. There is often a sense that something is about to happen. Not scary or dangerous, but a heightened awareness one doesn’t feel in the daytime. As a kid it was time to come inside, but I always wanted to stay out longer. Of course once I began making pictures, I had a perfect excuse to stay out and experience the shift from day into night.

For night photography, in particular urban scenes, there is a perfect moment for a photograph when the sky dims and the lights come on. Captured too soon, and the lights have no effect; too late, and there is too much contrast, and the lights will appear too bright. Often, it's a waiting game and then a case of working quickly to capture the decisive moment. Most of my early work was done this way, but not without disappointments, such as lights not coming on after waiting all day or cars parking in front of your scene, something that happens very often!

One thing I have always liked about low-light work is that once the sun rises, the mind can rest; there is closure, unlike a street photographer who is always looking and ready with the camera. Breakfast never tasted so good after a night of photography, followed perhaps by a bit of sleep, unless that is, you like sunrises!

The Turd

Gas Station, Death Valley. Scanned from C Type contact print.

My first purchase of Photoshop was on a CD back when computers had a slot so you could also watch DVD’s. It was a straight forward affair. You just popped in the CD, downloaded the software, and then maybe gave the CD to someone else to download. Well maybe I did, maybe I didn’t, maybe I was originally given the CD by someone else. It was the 90’s and I don’t really remember. These days things are very different and everything is virtual and apparently in some cloud. I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who upgraded their computer to find their 6 version of Photoshop could no longer be used and therefore had to rely on the workings of the cosmos and the newer constantly upgrading system. I liked the CS6 version, I liked the older versions. In fact, if I could still use the 03 version, I would, especially considering the most I do is a little bit of color alteration and maybe use the healing brush to remove a dog turd. This morning I upgraded to the latest 2024 version of Photoshop. It has taken Adobe 25 years to create this new monster and now there is no knowing where it will stop. I am of course talking about the new AI tool and in particular the constant pop up to remove the background and replace it with flowers, or a sunset, or a dog turd.

Technology has always set about to make people lazy in body and mind and this is really no different. I don’t fear AI one bit, I just like boundaries and making my own images.

Where will it go from here? Is it down to the lake I fear…

The Green Station Wagon.

Green Station Wagon. UT 2006

Arriving on the scene, the sun had not yet risen. It was -10 degrees, pitch black and very still. Waiting for the sun to rise, I jumped up and down on the spot for what seemed like hours, until, finally, the sun began to rise and I set the focus of the 8/10” view camera. As the golden sunlight illuminated the mountain, I loaded the camera and pulled the dark-slide waiting for the optimum moment. Seconds later a green station wagon pulled into view. Then, the driver, Chuck, got out of the car and came over to greet me. At that moment I clicked the shutter.

One of the joys of photography is capturing moments never to be repeated, what I call trophies. It may come as a surprise that these moments can happen in landscape just as much as say a portrait. Over the years these trophies have made up a large part of my work, but often no one really knows as they often look intentional, just like the Green Station Wagon.

The most interesting thing about this image is that had I arrived at the location and the car was already there, I probably wouldn’t of photographed it.

Spooky

Spooky Trees

Being Halloween, I tried to find something ‘spooky’ and this image was the best I could do. To most people this image will not appear at all spooky. But at 3.00am in a deserted car park somewhere in the Mojave desert, it certainly felt spooky, and creepy, and quite cold. What you do not see is the car parked behind me and the man watching my every move..

Creating a narrative after an image was made is fundamentally easy. In fact we can often make an image be about anything we choose (like a spooky tree scene) despite the original reasoning being something completely different.

I have yet to come across anyone who has produced exactly what they set out to do right down to the last detail. When I do I will let you know.

Something that shouldn’t be there..

Archive images 2000 onwards

In a time of reflection (a birthday), I have spent the last few days looking over my catalog of work putting together a portfolio of work made in the desert. I have been making work in the dry heat now for thirty years and have yet to grow tired from the images. On my first trips to the California in the 90’s, it was always the desert that called me to make photographs. That calling has never left.

Often the images I produce in the desert don’t look like the desert at all, well not the desert most people think of. I don’t have any images of a large cactus, or sand dunes (maybe one or two), or people on camels. just give me something that shouldn’t be there…

Sonoran Desert, Salton Sea

I saw the light

Winslow, AZ, 2023

As a landscape photographer, my images have always been about light, be it the early morning glow from the sunrise or the eerie dim of a street lamp. My fear is that in a digital age, this capturing of light is becoming a lost art. Film captures light and records it, digital copies the light and recreates it in pixelated form. No matter how many ‘mega’ pixels we use, this will always be the case. As a result, this ‘copying’ the light in a digital image is very easy to manipulate. No only that, we can add light, or take it away just as easily when it comes to a digital file.

As a young student I was taught that studio lighting should always mimic daylight. A good skill to learn growing up in the North of England where the sun often hides (although since moving to California I have never stepped foot in a studio). Like digital copying reality, the studio light also copies a reality (the sun) and creates something which may look the same, but is not. If we use one studio light and mimic the sun (one light source) we can copy what the sun does. But if we add another light we are creating something else. Now throw digital into the mix and we are suddenly very far from what is real..

Natural light can be unpredictable. It can be warm or cold, flat or contrasty, sharp or soft, and sometimes capturing it rather than copying it can be wonderful.

The stained glass window effect.

Its hard to imagine a time when photography was all about the print, (the irony being that here I am showing digital images). Back in the 90’s I had a commercial darkroom and spent are large amount of time perfecting the art of printing. (Thankfully I still have a darkroom and still find joy in printing). For me there is nothing like holding and looking at a good print, but I will also be the first top admit that more often than not, an image on a screen will look better. The stained glass window effect of a backlit image such as a night shot will knock the socks off a print in terms of impact, but I will take the print over a virtual image any day.

Something to talk about.

Vegas, 2000

Over the years I has learned that every photograph, no matter how simple, planned or even accidental, has a story behind it. Sometimes the story is a simple one, sometimes it could fill a book. But these stories are often the engine that drive our image making, why? Because who doesn’t like a story. But its not just the image maker that tells the story. There are usually two types of story behind a photograph, the obvious one being a photograph that is displayed in someones home, be it a family portrait or an epic landscape. Often the image will relate to some event, a fictional anecdote perhaps. The other story, and one that relates more to my own work, is a photograph that someone else has made. Here you have the story from the artist, and then maybe the story of how the image was obtained, a combination of fiction and non fiction.

But no matter what the story is, it always comes after the photograph has been made. The photograph introduces the narrative and basically gives us something to talk about.

Unlike the moving image were things need to be continually moving, the photograph introduces the story, tells the story, and leaves us with an image of that story in one single frame.